This second book of the series explores the regional variations of Day of the Dead in two regions of Oaxaca: the Central Valleys and the Isthmus of Tehantepec.

This second book of the series explores the regional variations of Day of the Dead in two regions of Oaxaca: the Central Valleys and the Isthmus of Tehantepec.

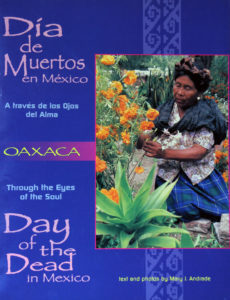

The book includes essays and over 95 color photographs of Biquies, tombs, artisan works, rituals, costumes, and typical foods used to express the continued connection between families and their deceased.

Written in English and Spanish, the book details the contrasts between Day of the Dead in the Central Valleys and “All Saints Day” in Tehuantepec: The differences between the altars and biquies as well as the colorful activities at the produce and flower markets, to the exceptional rituals of the night vigils at the cemeteries.

“Evolution of the Altar

“To the Tehuanos, descendants of the Zapotecs, Xandu Ya—All Saints—death is not a reason for mourning. But rather, Xandu Ya is a reason for celebration in all homes, having the opportunity to remember and honor the memory of their ancestors.

“Throughout the year, when somebody dies, aside from the traditional altar displayed at this time of the year, an All New Saints altar is also set; a ritual in which all family members play an important role. The All New Saints altar, as previously mentioned, is set up for the relative that died during the current year and at least forty days have passed since his death until October 30th.

“Throughout the year, when somebody dies, aside from the traditional altar displayed at this time of the year, an All New Saints altar is also set; a ritual in which all family members play an important role. The All New Saints altar, as previously mentioned, is set up for the relative that died during the current year and at least forty days have passed since his death until October 30th.

“On the eve of the celebration, October 31st for the children or November 1st for the adults, friends of the person who is going to prepare an altar gather and offer their support by means of either contributing with the preparation of the tamales, the atole, or by helping with the decoration of the altar. This type of neighborly assistance is called in Zapoteca chagalu, a sharing attitude, known in other places as toque del vecino.

“In the afternoon of October 31st, women gather to make arrangements for the preparations of the tamales and atole de leche (corn starch drink made with milk) for the following morning. Friends and relatives who help and contribute are welcomed with these treats on either November 1st or 2nd.

“Several people help with the decoration of the altar, while a group of women grind corn, separate the spices, and prepare the mole. At dawn the follow-ing day, the women gather once again to prepare the tamales. They spread the dough on banana leaves and fill them with chicken and mole, which was prepared the previous night. By 9 o’clock in the morning, everything is ready, just in time as visitors start arriving to pay their respect to the deceased.

“Several people help with the decoration of the altar, while a group of women grind corn, separate the spices, and prepare the mole. At dawn the follow-ing day, the women gather once again to prepare the tamales. They spread the dough on banana leaves and fill them with chicken and mole, which was prepared the previous night. By 9 o’clock in the morning, everything is ready, just in time as visitors start arriving to pay their respect to the deceased.

“November 2nd is a day filled with much pomp and circumstance, since the souls of the adult are received with some apprehension. Until recen tly, parents would tell children to be very careful on this day because the souls of the deceased would be returning to live among the relatives.

“In Tehuantepec, the altars take the form of a pyramid, due to their pre-Hispanic roots and the fact that pyramids were the center for religious ceremonies before the arrival of the Spaniards.

“The base of the altar is a big table, placed close to the wall with boxes on top forming two steps. From the table to the floor, there are another two steps or levels, a total of five stairs from the floor going up.

“The Zapoteca ancestors believed “life was sustained by death,” depicted in the altars by the five steps, an illustration of life’s cycle. The first level represents birth, the second level represents life, death is represented by the third level, the fourth level rep-resents the transition period and purification of the soul, and the fifth, the return to a new life. The last concept has a profound meaning.

“The Zapoteca ancestors believed “life was sustained by death,” depicted in the altars by the five steps, an illustration of life’s cycle. The first level represents birth, the second level represents life, death is represented by the third level, the fourth level rep-resents the transition period and purification of the soul, and the fifth, the return to a new life. The last concept has a profound meaning.

“A picture of the deceased being honored is placed adjacent to the family’s religious images of their devotion. Candle holders are placed in each level and at the foot of the altar are large candles. On the floor there is an arrangement of flowers in the form of a cross, in the same manner as it was done for the nine-day vigil after the burial in the home of the deceased.

“From a religious perspective, incense is an important item that produces a fragrant scent during prayers as the ceremony begins at the foot of the All New Saints altar. The person in charge of the prayers arrives prepared to guide with expertise through the mysteries of the holy rosary, as relatives and friends of the deceased follow in unison.

“As far as the food is concerned, favorite dishes of the deceased are placed at the altar. If the deceased was a child, his favorite toys and candy are displayed. If the deceased was an adult, along with the food, coconuts and machetes to crack them open, beer, mezcal and cigarettes are included. Originally only tamales and hot chocolate were offered; later alcoholic beverages and cigarettes were added.”

“Mary J. Andrade has succeeded in giving life with great journalistic skill to the vibrant flowers in the markets, to the joy in the hearts of the women, to the creativity with which the altars are set in Tehuantepec and Juchitan. With sublime and multicolored expressions, Mary J. Andrade has created true literary mosaics,” writes César Rojas Petriz.

The book includes several poems by Spanish poet Julie Sopetran.

ISBN 0-9665876-1- 8

Copyright 1996

Paperback, 87 pages

Price $32.99

Includes tax and shipping.